- Nikita Sonavane

- Sep 16, 2024

- 24 min read

Updated: Apr 14, 2025

This lecture was delivered as part of the seventh annual History for Peace conference titled 'The Idea of Justice' at Tollygunge Club, Calcutta, 2023.

I would like to talk about an institution which is a part of our daily lives and our imaginations—the police in India, and questions relating to what it is, how it came to be, who are the people implicated in it and where are they leading us. I will be drawing on my work and perspective as a criminal lawyer, researcher and co-founder of the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project (CPA Project) in Madhya Pradesh. My entry point is through the idea of casteist policing, or Brahminical policing, in particular the targeting of more than 300 communities listed as Denotified Tribes (DNT), or as until 1952, the Criminal Tribes. Though these once-criminalised communities prefer vimukta meaning free as a term of self-assertion, I will use the administrative category DNT to underscore its deployment through everyday policing. My focus will be on the criminalization of the DNT in the context of alcohol policing, which is regulated through the Excise Laws formulated by different states. My particular concern is the Excise Act of Madhya Pradesh. Formulated in 1915, it continues to remain in force. I would like to examine how this colonial idea of group criminality came to be, how it culminated in the criminalization of the DNT and how the linchpin of all this is the institution of the police, and more importantly, the institution of caste.

The label attached to many DNTs is ‘habitual offender’; also ‘rowdy sheeter’ or ‘gunda’, to name only a few. Clearly, a nebulous category exploited wholeheartedly by the police, the media and, more recently, even OTT platforms such as Netflix.

Before I proceed, I would like to tell you how I arrived at these questions. I don’t belong to a DNT, and so this kind of criminalization is not a part of my everyday reality or lived experience.

In law school, one’s imagination is severely stunted. There is an exaggerated sense of self-righteousness in the belief that by practising law in court, we can save the world. There was an ongoing case of institutional murder which had occurred in 2017, in Bhopal. A woman named Indramal Bai from the Pardhi community died a few days after immolating herself due to police harassment. In her dying declaration to the magistrate, she said that four police personnel from the local police station would regularly turn up at her house and demand money so as to not charge her with various cases. Being a single mother, she had no money to pay them and one day, when she’d had enough of their harassment, she set herself on fire. She emphasized that the police aided and abetted her suicide.

In order to prosecute a police official, one needs prior sanction from the police department—in this case, the Madhya Pradesh Police Department. Needless to say, the sanction was not given. So, the Pardhi community in Bhopal led a writ petition at the Madhya Pradesh High Court demanding a First Investigation Report (FIR) against the police officials whom Indramal Bai had mentioned in her dying declaration, for abetment of suicide. But the defence for the accused said in court that Indramal’s dying declaration could not be believed or accepted because she was a habitual offender and belonged to a criminal community. In any other instance, the court wouldn’t have entertained such an argument. But here the court regarded this as a valid point and sought to delve deep into her criminal antecedents, only to discover that she had been acquitted and found ‘not guilty’ in all of the nine cases against her (there were some cases still pending at the time of her death).

This clearly shows how a certain category becomes so marked, and so deeply embedded in the popular psyche, that a section of people, despite being the victims, simply do not get justice via the judicial process.

The origin of this category of ‘habitual offenders’ takes us back to the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA).The CTA, formulated by the British in 1871, branded several communities—nomadic and semi-nomadic—as hereditary criminals. A list was issued with the names of over 200 ‘criminal tribes’ across the country. In West Bengal, the Kheria Sabar community was classified as a Denotified Tribe. Budhan Sabar, a member of this tribe, died as a result of custodial violence in police custody.The CTA was also used in other colonies by the British and there is a history behind the logic of hereditary and occupational criminals. But in its embodiment in the Indian context, it tapped into what was already available—the logic of caste. According to the caste system, occupation is assigned by birth; hence, some are priests, some warriors, some others merchants, etc. But many of these tribal communities didn’t ascribe to the caste system. Because they lived outside the caste hierarchy, they were thus occupationally designated as criminals and the colonial authorities sought to render them sedentary—they created settlements—criminal-tribe settlements—akin to the detention camps that continue to exist in the country. [1] And so children were separated from their parents; the detainees had to take permission to step out of the camps; there were roll calls and attendance was monitored; and of course, they were subjected to hard labour.

One significant result of the CTA is the creation of ‘criminal registers’. Every police station had to maintain a criminal register in which it recorded and regularly updated, all available information about these people: their descriptions, birthmarks if any, their fingerprints, their friends/families, their movements.This persistent collection of data by the police has been crucial to creating the archetype of the habitual offender.

The CTA has also contributed to the institutionalization of the police as we see it today. Earlier, policing was decentralized in the village, using local governance structures such as the patwari, or village registrar. But the British realized that to maintain control in a concerted manner, an institution with a certain framework would be required. So, they used the model of the Irish paramilitary force and created a centralized police force. [2] Despite this, there was fear: many members of these criminal tribes had participated in the Revolt of 1857, which was an added incentive to crimalinalize them.

The CTA was amended several times in 1894, 1911 and 1924 and every amendment gave the police more and more power. On the cusp of Independence, the Constituent Assembly was set up and the question of the criminal tribes was debated. As historian Sarah Gandee has argued, [3] most members, such as Dr Ambedkar, who advocated for the rights of oppressed castes and untouchables, and Deshbandhu Gupta, supported these restrictions imposed on the movement of these criminal tribes, in the event of them being a source of danger to other law-abiding citizens. Gandee adds that only one member, H. J. Khandekar, who belonged to the Untouchable community and was a member of the Indian National Congress, championed the cause of the DNT. For this he faced immense opposition because prejudice was rife in the government. Nehru also opposed the idea of terming tribal people as criminals, as it would be politically incorrect and not befitting for the idea of a postcolonial nation. Yet, Nehru agreed to the idea that these people might be criminals from birth and wanted to devise a more ‘administratively neutral’ way of criminalizing them. Hence, the category,‘habitual offenders’.

The government set up the Ayyangar Committee [4] from 1949 to 1952, also called the Criminal Tribes Act Enquiry Committee. It decided to put the DNTs into the category of habitual offenders, which was deemed a more administrative and neutral category.This is the origin story of the habitual-offenders category.Various states formulated it into their legislation, such as Madras, Punjab, Rajasthan and Bombay. Provisions were also inserted in the Code of Criminal Procedure or CrPC.

To exist as a habitual offender in this country means to be under constant surveillance.The police can show up at any time to one’s house; one can be summoned to the police station if there’s a theft in that particular area.The volume of information collected by the police in this manner has only increased now. The data includes: who your friends are, who you talk to, what kind of phone or vehicle you own, what your father and uncles do, if somebody has been in prison then who his prisonmates were and if he is still in touch with them, as well as information about children.The Juvenile Justice Act in India says that an offence committed by someone below the age of 18 cannot be a part of his criminal record in line with its principle of ‘fresh start’. But this doesn’t apply to people termed habitual offenders nor to the children from these communities. One would be an offender if the offence has been proven in court, but in the case of these people, being found guilty by a court is not a prerequisite.

This brings us to an important point—the discretionary power of the police.Theoretically, anybody can be a habitual offender if the police think that person to be dangerous, having a bad character or disrupting peace in a particular place.The police need not offer much evidence of this, as these are all considered preventive measures.This is an overturning of the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’, while surveillance impinges on all aspects of these peoples’ lives.

Criminalization is thought of only in terms of incarceration—if you’re criminalized, it means you are in jail. Many of the people termed habitual offenders haven’t spent a significant amount of time in prison. But they can’t go to the local market because there’s police surveillance. If there’s a wedding in the Pardhi family, they have to submit an application to the local police station along with the wedding invite and guest list. Because it is assumed that if a group of Pardhis congregate, they might conspire to commit a crime.This is not just a phenomenon in Madhya Pradesh. The Andhra Pradesh Police Manual notes the same, as well as in many other parts of the country.The section titled ‘History sheeted Persons – Reporting Movements’ in this manual reads:

The beat Police Officers should be fully conversant with the movements or changes of residence of all persons for whom history sheets of any category are maintained and those whose names are entered in Part III of the Station Crime History. They shall promptly report the exact information to the SHO and make entries in the relevant registers. The SHO on this basis and/or on the basis of the information gathered by himself should report by the quickest means to the SHO in whose jurisdiction the concerned person/persons are going to reside or pass through. After sending the first report a BC Roll inform A (Form 109) should be despatched to them by speed post or courier ser- vice.The SHO who receives the first communication should acknowledge the communication and inform the concerned beat Police Officers of the area. After he is satisfied that the change of residence has been effected or that the subject has moved out to another area he shall report the details to the SHO from whom he received the communication. If the subject is moving out to another area he should initiate the same procedure of intimating the concerned SHO.The receiving officer shall acknowledge the first and second communications. If he takes temporary residence within the limits of another station, his name should be entered by the police of the latter station in the register in Form 113. When replies are received the SHO shall make necessary entries in the history sheet and records. When a history- sheeted person is likely to travel by the Railway, intimation of his movements should also be given to the nearest Railway Police Station. [5]

At present, the police have linked the Aadhaar numbers of all of the rowdy sheeters and linked those to their SIM cards. So each time a rowdy sheeter moves out of a particular police station’s jurisdiction, the police know it in real time. Using AI technology, the police track their movements, and report them to other states. If a habitual offender has moved to another state, the police department of that particular state will report to the other state.The Andhra Pradesh and Telangana police have such reciprocal surveillance agreements with states like Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

There is the fear of the bad characters going out of view, so authorities issue ‘out-of-view cards’. If one moves out of the jurisdiction of a particular police station and the police can’t trace that person, he has to be given an out-of-view card. But these are all nomadic communities who have always been on the move, primarily for the sake of their livelihoods. Many are street entertainers, traders, and hence, part of the informal economy. So people like the Saperas and the Madaris, who work with snakes and monkeys respectively, were all classified as DNTs. Whatever constitutes our informal-economy sector is occupied by these nomadic and semi-nomadic communities who have been criminalized through various laws. Projects such as the Aadhaar card is an extensive surveillance project that has been rightfully critiqued for impingement on our right to privacy. This critique of surveillance mechanisms is a historical right because they have existed long before Nandan Nilekani and his clan conceptualized the Aadhaar.

Under the CTA, children born into families of criminal tribes were separated from their parents on grounds that they needed to be raised in a ‘more wholesome atmosphere’.[6] There were executive orders that were passed—about how the children should be treated and taken into custody by the State if disposed of by parents for money, or separated from parents. Besides all the surveillance, the police also have to charge these people with o ences, creating a pretence of registering a FIR. One of the many laws that enable the police to do this is the law on alcohol policing—the Excise Act.

After the 2012 Jyoti Singh Pandey gangrape and murder, there was an uproar about the need for stronger criminal laws and more power to be given to the police to go after the predators and murderers. Movies have sold us a brand of policemen who pursue the big, bad guys and finally punish them. But as I started litigating and going to court every day, it all seemed far less glamorous than what we'd been watching on screen. At first, I was only handling cases pertaining to card games, gambling and alcohol consumption, 'petty offences' in legal terms. A significant part of this category is the Excise offence

The entire narrative around Excise offences comprises the idea that alcohol is bad, immoral and unethical, especially for a certain group of people unless it is at card parties in South Delhi. This narrative had to be controlled by the state because the sale of illicit liquor has to be controlled by the state too, for there have been many deaths in the country as a result of spurious liquor consumption. So my colleagues and I at the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project (CPA Project) began to examine how the police operated on a day-to-day basis whether they went after the liquor mafia or the people who consumed the liquor. All the police stations in Madhya Pradesh upload records of their arrests every day. So, we studied two sets of data between 2018 and 2020, spanning 20 districts: the arrest records and FIRs. We studied 5,62,399 arrest records from those 20 districts, along with 540 randomly selected FIRs registered under the Madhya Pradesh Excise Act. We tried to figure out who was being criminalized and why, and how this criminalization was being done.

We found two things. One, the majority of cases––92 per cent of the arrests or FIRs [7]––were registered for desi liquor of a particular kind: mahua, made by the Adivasi communities. One may imagine that vast amounts of mahua was being bought and sold, but the maximum quantity for which one was charged was only 10 litres. Two, the substance of the FIRs represent the limitations of human creativity, for they are all identical and standard for the same offence. A significant number of them claimed that the police found out through a mukhbir or informant that someone was in possession of alcohol. Or that a person holding a suspicious-looking packet of liquid had been arrested. The police smelt their hands and determined whether or not the packet contained spurious liquor. Possession of chakna or namkeen (salted snacks) was also recorded in those FIRs.

Possession of alcohol in this country is not an offence. Nor is Madhya Pradesh a dry state. If you're accusing someone of selling liquor illegally, then you must also establish the presence of a customer and an exchange of money. But in most of these cases it was simply individuals being charged for possession. One police station in Bhopal charged everybody for public drinking but that is not an offence under the Excise Act. 56.35 per cent those people belonged to the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes and the DNT communities. It was also very peculiar that the women from the DNT communities were charged excessively. The Ghamapur Police Station in Jabalpur arrested women from a DNT community known as Kuchbandhiya under the Excise Act and charged at least 25 to 30 cases against each. Kuch means rope, so this was a community of rope-weavers. But when they were pushed out of their traditional livelihoods, they turned to brewing liquor. The percentage of women implicated under the Excise Act and charge-sheeted in Madhya Pradesh is 8 per cent, whereas the national average of all women chargesheeted for all offences is 5 per cent.

It is more than evident that criminalization happens in a drastic manner within a common gendered imagination. The figure of a criminal is often thought of as a masculine one and women are considered incapable of crime. But this patriarchal trope is turned upside down in the case of women from the DNT communities. The CPA Project's study demonstrates that the women convicted under the Excise Act belong to the Kuchbandhiya and Kanjar DNT as well as the Gond, one of the biggest Adivasi communities in India. Only one woman belonged to an OBC and one other from a dominant caste.

We also wanted to see what happened in court when these women filed for bail. All bail applications were rejected with a single sentence: she is a habitual offender. [8] This goes against the reasoned order that courts need to provide when denying someone's liberty and ordering them to continue time in prison. We interviewed women from the Kuchbandhiya community to understand how this category of the criminal woman was being constructed. And they said that the police barged into their houses at night. After sunset, no male policeman can arrest a woman yet they drop in. The common perception is that the liquor mafia is at play and these women are at the helm of it. This trope of the women from these communities being criminals is antithetical to womanhood; they're projected as scrupulous, merciless and cruel, all qualities not stereotypically associated with women.

Ambedkar writes: 'An important part is also played by women, who, although they do riot participate in the actual raids, have many heavy responsibilities. Besides disposing of most of the stolen property, they are also expert shoplifters.' [9] While violence against women is always spoken of in terms of patriarchy, here we see how Brahminism is the point of origin of a violence perpetrated against lower-caste women. Women belonging to the lower rungs of the caste hierarchy are criminalized, and the kind of violence–nature and substance attributed to them is very different from when the woman is Brahmin or Savarna.

The construction of criminality, as we see in Indramal Bai's case, also stats in obfuscating the violence and harm experienced by these women. A long time ago, there was a similar case that had been written about extensively. In 1972, a young girl named Mathura from an Adivasi community in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, was subjected to custodial gangrape. The Supreme Court upheld the acquittal of the accused police officials by saying that she was promiscuous and of loose morals, and already in a relationship with the three rapists. [10] After the Mathura case, rape in police custody came to be recognized as a legal offence because it was taken up by the women's movement but the judgement in the case remained as it was and the officials were acquitted.

The Mathura case, among many, is vital to our understanding of the violence that women face, and consequently, to complicate the understanding about where the said woman is located. It is important to complicate these questions with questions of Brahminism. It is also necessary to understand what we mean by Brahminical constructions and how they play out within the site of the prison. All kinds of incarcerations are regarded as the same for every one but they are in fact not so. There are police manuals that delineate the differential treatment between prisoners based on caste. The prison manual of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana mentions that the caste thread of the Brahmins cannot be removed; that they have to be provided with a separate cooking place with separate aluminium or earthen pots, that Hindus should be allowed to retain their top knot, or the choti that a lot of Brahmins maintain. And that caste prejudice of prisoners should not be prohibited, including in the way that prison duties are allocated. So, if a Brahmin has been asked to clean the toilet, he can refuse, because according to his position in the caste hierarchy, he cannot be compelled to clean the toilet. This has been corroborated by conversations we have had with incarcerated people, Sukanya Shantha wrote a piece for the Wire in 2020, titled 'From Segregation to Labour, Manu's Caste Law Governs the Indian Prison System' where she examined the Rajasthan Prison Manual and pointed out how duties in prisons were allocated on the basis of caste. [11] So, the Brahmins would cook, while the lower castes would clean toilets.

Thus we see that caste is not only being enforced by the law, which is a common trope, but also that the law finds its origin in the caste system. While discussing terms like law and order, and punishment, it is important to unpack these categories to see what kind of law and order we are trying to enforce. Because, whether in the Excise cases or in the treatment afforded to prisoners according to their castes, it is actually social order masquerading as law and order.

So, my point is that, despite this kind of history, the immense empirical evidence that is available, why have we considered policing as only a colonial construct? When everyday forms of policing show that especially in the treatment of habitual offenders that it is both constituted and driven by caste? In the teaching and learning of the history of laws and law-making in our schools and colleges, we have actively avoided speaking of the Brahminical origins of this institution. And that, one might argue, also speaks to our own complicity in aiding and abetting this monster.

Question and Answer Session

Audience Member 1: My name is Sagnik, I am a museum educator but I have also done a bit of work on the Criminal Tribes Act, viewing it from a nineteenth-century historical lens.You rightly point out the Criminal Tribes Act, and its modern avatar—the Habitual Offenders Act—has its roots in Brahminical systems, and so does this prosecution and persecution of alcohol, etc. Does it also not carry the remnants of a very colonial idea of extracting value out of human beings, in the sense of productivity? In the Criminal Tribes Act, there is a set of noti cations that essentially target certain communities whom the colonial regime did not consider productive enough, like the Harinshikaris, stemming from the fear of itinerant communities. I think the Indian state too has that same fear.Would you like to comment on that?

Audience Member 2: The last part of your presentation was about how our colonizers created the idea that whatever was writ in the Brahminical texts should be taken at face value. And how under Hastings that moved from what could be called a theocratic under- standing of law towards a despotism of law, which seems to be reiterating itself now. And how many of the traces of the books they found law in continued, which includes the understanding of Brahminism itself as law. And while that continues, do you think that there are times when we try to draw distinctions between religion, law, criminal and something that’s entirely separate? Even though we are taught that each is separate, apart from personal laws which apply to divorce and marriage and property.What do you think about the blurring of these boundaries? Should they be blurred? And how will they be affected now?

Audience Member 3: Ama Ata Aidoo talks about colonization in the context of gender. She said that the colonial power and the power centres of the colonized agreed upon the place of a woman. So how do you see the colonizers’ structures of law and the existing social caste hierarchies interacting with these structures that you are talking about?

Nikita Sonavane: About colonization in the context of gender: the Infanticide Act is an important point of discussion and there is a sordid history of the colonial authorities tapping into existing structures of law and applying it in various ways. Padma Anagol writes how upper-caste women—predominantly Brahmin—were charged under the Infanticide Act for killing their children; it was considered a fall from grace.The Manusmriti advises the holding up a certain kind of honour, and sees the caste system as the linchpin in controlling the sexuality of a woman, especially an upper-caste woman. Because if the upper-caste woman acts out of caste lines or marries a lower-caste man, then caste purity gets disrupted. So, the idea of Brahminical purity attributed to women, especially upper-caste women, played out in a certain way in terms of law-making and legislative history. This is what I was also trying to demonstrate through the Criminal Tribes Act, and the way in which women of oppressed-caste communities are characterized as being devoid of honour, thereby precluding the possibility of their fall from grace.That’s what I mean when I say that colonial logic has beautifully tapped into the varying logics of the caste system and embedded itself around it through its law-making. In order to be able to critique the rationale of coloniality in a substantive or nuanced way, one has to be able to understand the heterogeneity of the position of women as well.

According to Manu, controlling the sexuality of Brahmin women is key to maintaining the caste system. Which explains the burning of the Manusmriti by Ambedkar on 25 December.The occasion is commem- orated by the Ambedkarite movement, and the anti- caste feminists celebrate the day as Bharatiya Stree Mukti Din or Women’s Liberation Day.What Ambed- kar wanted to say is that the burning of the Manusmriti is liberating the upper-caste women—and not the lower-caste ones—from the shackles of Brahminical patriarchy.

Caste or the force of caste operates through law- making. For example, the Manusmriti is about how to live a good and right life. People often say that Hinduism is a way of life, and that those prescriptions of the way of life are laid down in the Manusmriti. That is precisely the way in which law has always been embedded in a kind of norm. What, essentially, is caste, if not a set of norms? So multiple false binaries have been created to see law-making as such. It also upholds a convenient narrative that claims that everything was hunky dory until the British walked in. Life was great until the British came in and founded the criminal justice system.That’s when everything went downhill. One has to also consider the Thuggee narrative as based on the same instinct—that groups of people, usually nomadic, were criminals. It further embedded this idea of group criminality and laid the foundation for something like the CTA to eventually emerge.

My purpose was to speak about policing but also to underscore the point that we don’t operate as casteless entities. Ambedkar says very clearly that there’s no such thing as Hinduism; that, rather, it’s a conglomeration of caste.The Supreme Court is today hearing petition from Dalits, Muslims and Christians arguing for Scheduled Caste status. For a very long time, caste and the question of caste has been made to be synonymous with lower caste and lower-caste bodies. Hence, it is important to speak about the origin of caste which lies in Brahminism. One cannot understand what caste oppression is unless one understands Brahminism and how the lives of those who are privileged within the caste system are. Many anti-caste scholars advise under- taking ethnographic works in gated societies, and not in Dalit ghettos, in order to know more about caste. Because gated societies are where caste is formed, embedded and manifested and that is the kind of caste- less-ness which Dr Satish Deshpande points out. Through policing, certain bodies are masqueraded as being casteless.The idea is not that we are all DNT, but that we are all living in, embodying and operating through our respective caste identities.

Audience Member 4: Could you elaborate on the trajectory of transition in nomenclature from ‘DNT’ to ‘habitual o enders’? If you could also respond to the idea that women enter the framework of law as objects of security and not as subjects of law?

NS: In the building of a postcolonial nation, it would not bode well to replicate colonial typology and attribute criminality explicitly to members of a certain tribe. So, what we did was to sort of tap into what we under- stood as the essence of it. Which is: you tribes are habitually committing crimes and so we’re now going to call you habitual o enders.The rationale is the same as that of the British.You are habitually committing these crimes because you’re a born criminal. Be aware that there is a genetic attribute to it too. The CTA says that members of certain tribes who are criminals look a certain way: they have a protruding forehead, a big nose and other ‘physical attributes’. Multiple kinds of rationales are encapsulated in this nebulous category. Nowhere do they actually de ne a habitual o ender. Which means that the police have free rein to arrest anyone.

One of the first cases I worked on as a lawyer involved a young man from the Gond community, who had been charged with multiple cases for the theft of temple bells. Everyone said he was a serial temple-bell thief and they were all up in arms about him.Then, as it turns out, he was acquitted in one of the cases. But a couple of months later, the police station that had charged him, even though he had been found not guilty, summoned him to record his fingerprints, iris scan, retina scan and other detailed information. We asked: how can you summon him even after he’s been found not guilty? The police replied that they are not bound to follow the court; rather, they were required to monitor the o enders even outside the con nes of judicial overview.This encapsulates the way that this category is being formed, or re-formed, and this discretion is central to policing. It’s very hard for anybody to imagine a police system which does not have discretion. But we must look at how discretion only operates in a certain way. Discretion would suggest that there can be random outcomes. But how is it that, despite the discretionary power, the only alcohol that is criminalized is mahua, and not the alcohol that certain other people are consuming? And the only people being incriminated are those from certain oppressed-caste communities and not the privileged communities?

About women being protected by the law and not being subjects of the law: the protection of the law has always meant protection extended to a certain kind of womanhood and femininity. If one looks at judgements pronounced in sexual-violence cases, one will see that the rationale of the good Indian woman who can’t lie and therefore has been subjected to sexual violence, is the rationale that is very clearly operating in the case of upper-caste women.Whereas if you consider the case of Bhanwari Devi: the court very clearly said that a Brahmin man would never touch an oppressed-caste woman, let alone inflict sexual violence upon her. So the idea of who is deemed worthy of protection and who is not is also the language commonly used when men from upper-caste communities inflict sexual harm on women from oppressed-caste communities. It’s an exercise of a right and not a matter of transgression. As the court said in Bhanwari Devi’s case: it’s something that cannot happen because Brahmin men are only going to operate within those confines.This is very important for us to unpack and not to think of protection by the law as an all-encompassing phenomenon. It’s not and I think there is ample evidence that proves that it’s not.

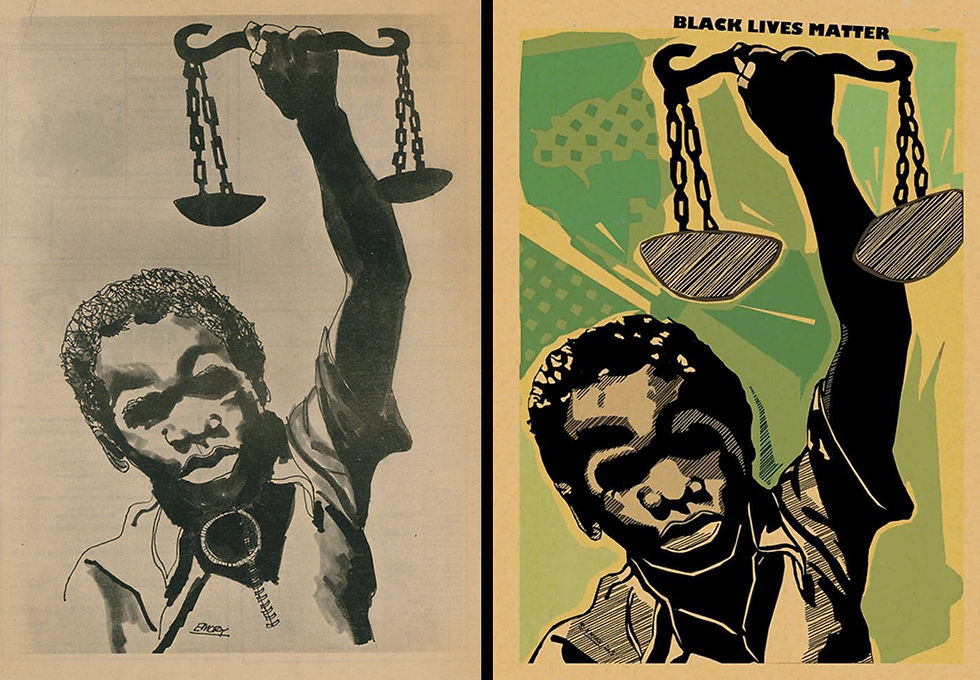

Audience Member 5: I’m wondering how we take this into the classroom. I always think of a parallel to the Abolition Movement, the Black Lives Matter movement in the US when I hear about your work. So, in the US, I think at lower-grade levels, at least in the liberal states, children are reading books by abolitionist writers and grappling with the idea that the police are not a friend. But that is not what we are teaching our children, at least our upper-caste children.

NS: Because we’re in denial about caste. In the US, there is, at this point, a consensus around the fact that there was, and there continues to be, racial violence and dis- crimination. Here, for the last 70 years, we’ve been incessantly debating the right of marginalized communities to education in the form of reservation.We have never moved to any of these other questions. Unless we can snap out of that collective denial of those who’ve benefited from this system, we’re not going to be able to even consider these other issues. In the US curricula, they’re not speaking about only African American students or lives—there’s a significant amount of work done also on whiteness and what it means to be a white person. On whiteness, which many of us for a long time have assumed to be the default. We’ve been able to do that in the case of queerness, we’ve said that heteronormative ideas persist, but we’ve not been able to proceed further and say that heteronormative ideas and all other ideas have Brahminical foundations.

For a very long time, Brahminism has been understood to be the norm, to the extent that it is considered to be a way of life and therefore not a question of caste. And I think that this is a really important starting point. So I want to speak here about implicating those who have been in these systems and those of us who have benefited from these systems. Because you can’t understand what has happened at the bottom unless you start from the top. Doing that in classrooms with students, particularly those from privileged backgrounds, is very important. Because they have never been taught to think about power in the first person, always in terms of the marginalized. And that thinking of power in the first person and that articulation would be a really good start.

Notes

1. Sumir Karmakar, ‘Assam starts shifting declared foreigners to India’s biggest “detention centre”.’ Deccan Herald (20 January 2023).Available online at:https://bityl.co/Qf2J (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

2. K. S. Subramanian, ‘The Sordid Story of Colonial Policing in Independent India’. The Wire (20 November 2017). Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf2N (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

3. Sarah Gandee, ‘(Re-)De ning Disadvantage: Untouchability, Criminality and “Tribe” in India, c.1910s–1950s’, Studies in History 36(1) 71–97 (2020). Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf2T (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

4. M. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar, Venkatesh Narayan Tivary, J.K. Biswas, Gurbachan Singh,A.V.Thakkar and K. Chaliha, Report: the Criminal Tribes Act Enquiry Committee, 1949-50 (New Delhi: Government of India, Manager of Publications, 1951). Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf2r (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

5. A. P. Police Manual, Standing Orders. Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf30 (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

6. Meena Radhakrishna, ‘Surveillance and settlements under the Criminal Tribes Act in Madras’. The Indian Economic & Social His- tory Review, 29(2) (1992): 171–98. Available online at https://bityl.co/Qf36 (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

7. Drunk on Power: A Study of Excise Policing in Madhya Pradesh. A Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project (2021). Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf3F (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

8. Srujana Bej, Nikita Sonavane and Ameya Bokil, 'Construction(s) of Female Criminality: Gender, Caste and State Violence', EPW 56(36), 4 September 2021. Available online at: https://www.epw.in/engage/article/constructions-female-criminality-gender-caste-and

9. ‘Civilization or Felony’ in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches, VOL. 5 (Vasant Moon compiled) (New Delhi: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, 2019 [1979] ), pp. 127–44; here, p. 133. Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf3d (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

10. Supreme Court of India. A. D. Koshal, Tuka Ram and Anr vs State of Maharashtra on 15 September, 1978. Available online at: indiankanoon.org/doc/1092711/ (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

11. Sukanya Shantha, ‘From Segregation to Labour, Manu’s Caste Law Governs the Indian Prison System’. The Wire, 10 December 2020. Available online at: https://bityl.co/Qf3w (last accessed on 22 June 2024).

Nikita Sonavane has worked as a legal researcher and an advocate. She is the co-founder of the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project (CPA Project), a Bhopal based litigation and research intervention focused on building accountability against criminalization of oppressed caste communities by the police and the criminal justice system. Nikita has previously worked on issues of local gov- ernance, forest rights and gender in Gujarat. She graduated with a BA (Political Science) from St Xavier’s College, Bombay, LLB from Government Law College, Bombay and an LLM degree in law and development from Azim Premji University (APU), Bangalore. She is a visiting research fellow at the University of Oxford working on anti-discrimination law in India. Her writings have been at the intersection of policing, caste and digitization of the criminal justice system in India and have been published by the AI Now Institute at New York University, Indian Express, The Hindu and The Caravan among others.

Comments