- History for Peace

- Jul 14, 2023

- 30 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2024

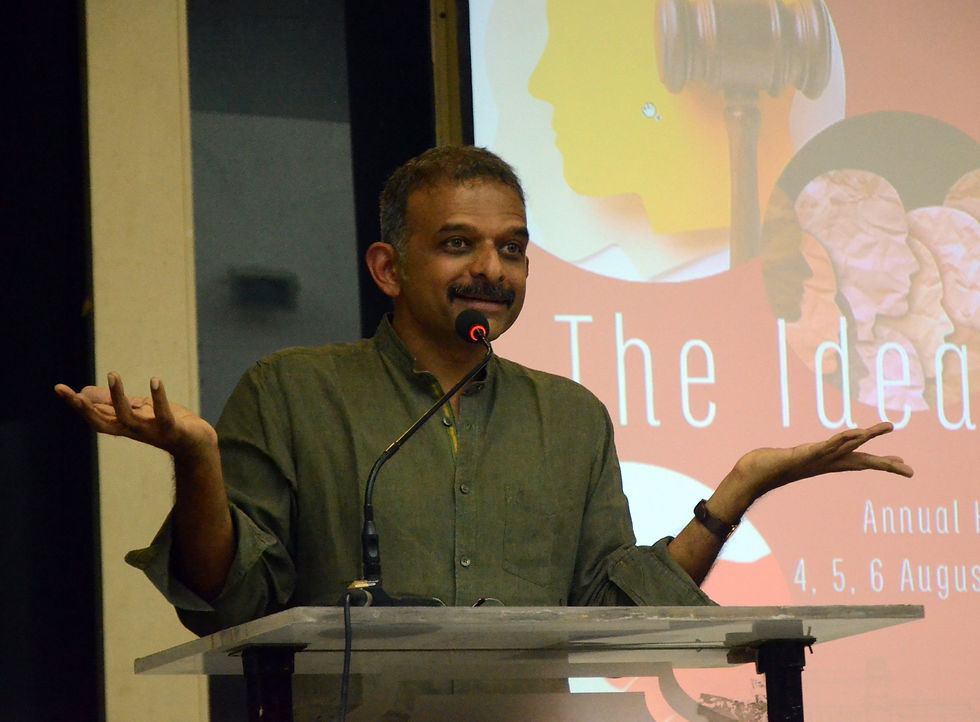

This lecture was delivered as part of the 6th annual History for Peace conference titled 'The Idea of Democracy' which was hosted in Calcutta through August 4, 5 and 6, 2022.

Good afternoon and thank you for inviting me to the conference. I looked at all the speakers and I am the only one who is not a professor, so I have a distinction among all the speakers. It can be an asset but it can also be a little debilitating—I don’t know which side it will go today. I’ll start with a conversation Naveen and I just had at lunch. I was standing and having lunch when Anu asked me: Why don’t you sit and eat? I refused, saying that I prefer standing and she said you prefer standing? Naveen shared that when he was growing up, he was told to have his morning milk and raw egg while standing because only then would it go to the extremities of the body. I informed that I was told to not stand and eat because if I stand and eat, the food will all go away to the ground. This defines my talk today: These two descriptions of standing and eating seem so simple but they define the idea of what we vaguely call ‘culture’—I’ll keep saying ‘vaguely’ because I don’t think I really understand ‘culture’. Do any of us here really have a hang of it?

But the experiences—both his and mine—of being told this in childhood and later reminding ourselves in a very funny manner, habitually, is something that is going to live with Naveen and me and both of us will look at it in two different ways. The reason I began with this anecdote which happened totally accidentally before my talk is because we speak of Indian culture—we have been speaking of Indian culture for over a hundred years or even more. It is not a new construction. We have never said Indian ‘cultures’ in the plural, we have said Indian ‘culture’. Therefore, we have to address what seems to be everybody’s understanding of ‘Indian culture’ and what seems to be very contradictory to Indian culture—like whether we should stand and eat or not. I would be speaking entirely from the position of being an artist, therefore there will be a lot of ‘I’ in the talk—not because it is egocentric but because I believe I am one of the participants in this construction of what we have been told to believe is Indian culture. Or in other words, I will call myself the establishment—I am the establishment and I will speak as an artist from this notion of the establishment. Hence, what does it really mean?

How do I grapple with the idea of freedom, democracy, culture, art—everything seems so muddled in one another. The thing about art and why art is important in this conversation is it is by default presented, it is the performative of what we perceive as culture. The performative can be private—it can be a lullaby at home by untrained artists. The performative can also be from trained musicians, dancers etc. Art, in a way, is a kind of an externalization of what we believe inside as culture. Therefore, it kind of is a very important cog in our understanding of what this is all about. Let me take a step back here because the moment I say art, I can just imagine all the imagery that comes in your head—probably a song, a painting, temple, church, could be a place you went to, could be anything—there all these things that rush in. But when I, as an artist, speak about art and the experience of art, what am I addressing? So, when I sing or when someone receives my music, are they receiving art? It seems like a very fundamental question. Are they only receiving art or are we sharing something much more complicated? Art itself is not formed in vacuum: it is formed in context, in co-habitation, in osmosis, in sharing. But when we experience it, we are not looking at that even if we may know all this intellectually. When I sing a song, somebody cries. Sometimes, the reason I sang the song and the person crying has no connection. For example, people have come and told me, when you sang that song, I saw Krishna in front of me. I never thought of Krishna, so where did Krishna come from? Was Krishna embodied in the music that was produced or was Krishna embodied in the receiver? It is a very interesting, non-paradoxical, philosophical question but we have to grapple with it because all our cultural habits are similar. I want you to naturally extrapolate this to many other things that you would be doing in life—it need not be music. So the question that I have to ask myself is: What is it I am doing on stage, what am I doing when I sing a song, what am I doing to myself and what are the possibilities of what it can do in the sharing—I have no control over it.

So, in the experience of art, a very important relationship is formed between what is being given out by the artist—I would call the artist the catalyst rather than the producer of anything—and the person who is receiving it.

Many times, what we are doing is not just receiving a melody but receiving memory. We are receiving memory, context, families, community, gender, sexuality from just listening to a song or going to any place. So, in a way, the experience itself is a construction. And the construction fortifies the experience. It works both ways and it is in this dual relationship that we do what culture wants us to do most—become habitual. The reason I am saying this is that your art gives this whole feeling of going somewhere else, like we are not part of this reality. I will address that issue too. Therefore, the entire thing is constructed. I am not passing judgements over that construction—not saying it is bad, good, ugly, it shouldn’t be this way. But we have to be aware that it is constructed which means it comes with greys all over. You may draw pleasure from that construction but you are part of that construction. I may enjoy giving you that but I am constructing something. So there is a responsibility of awareness that is required for every participant in that cultural or artistic construction.

Let’s look at another seeming paradox. When I feel I am part of this art culture, there is an identity formation. We form an identity as a collective—that identity gives us a sense of safety and somehow, we believe that safety gives us freedom. Now, here is the paradox. Identity by its very nature is a constricting notion—it is a notion that puts you in a box, in a certain bracket. But somehow, it is our association with that identity that makes us believe we are also free to be who we are. This is a very interesting thought. We can speak in philosophical frameworks and say that identity is an issue but I want to raise this because we experience this—we feel safer, more comfortable (when we associate with an identity) and therefore we can say what we want. For example, there might be some things you will say here which you might not say somewhere else where there are not people like you. So, the question is: Is this also part of some kind of a trap? Of course, I would say that is not freedom because what you are actually expressing is a collection of their identity rather than yourself—that is an entirely different track of conversation. The question of freedom also comes into this dialogue of culture and art and its associations and what happens.

As much as I’ve said all of this, I would be lying to myself if I don’t say that when I am singing, at that moment, even when I am aware of everything I have uttered to you today with which you may agree or disagree, there is something that makes me free. As much as it is constructed, as much as I know that I am part of it, when I sing, at that moment there is freedom. I am going to leave that thought around and come back to it because that is an important aspect to discuss. So, in a way, just like we have constructed that experience of culture, of art, I think democracy is the construction of freedom. We have tried to construct the idea of freedom through this mechanism. So, is it freedom? This is an important question to ask ourselves because we can’t just digest this notion that democracy is freedom or democracy leads to freedom because it is a construction. Let me now go back to the way I learned my music because like I said, I am speaking from the establishment or the dominant or the majoritarian—you can use any word you want—point of view.

I grew up in what I would call a typical cosmopolitan home, traditional in the way cosmopolitan people like to call themselves—the snooty traditional. A friend of mine calls me the English-speaking Brahmin—I think that is a very good definition of myself. I grew up in that home where of course we were anglicized—we spoke English more than we spoke Tamil. Carnatic music, which I sing, was part of that construction of culture but it was not similar to the construction of a middle-class Brahmin home or a lower-middle-class Brahmin home where its role is different. You have to recognize that there is a difference between what Carnatic music is to a middle-class Brahmin home and what it is to a cosmopolitan Brahmin home—very different frameworks. There will be no musicians in my family because we are the patrons, right? I grew up in such an environment, happened to start learning music at a very young age. My teacher came from a very traditional background from Andhra Pradesh. My entire world was very interesting: in one part of my world, I was going to a J. Krishnamurti school in Chennai; the other part of my world is Mylapore, which is a metaphor and not just a location. Mylapores exist even in Kolkata, they exist everywhere. For those who don’t know, I will tell you what Mylapore is: It is a suburb in Chennai that I would define as representative of what would be Brahmin upper caste culture, societal practices and tradition. This is as vague as it can get and Carnatic music is seated in it because it belongs to that group and that is true of many art forms across the globe.

So, there is one side of me that is Mylapore and there is another side of me that is going to a J Krishnamurti school where Mylapore exists in very different ways but not in this way. This was a very interesting experience for me to grow up in and my home is interspersed somewhere in between these two worlds—possibly a world of its own. I keep thinking about what I learned at music class. Of course I learnt music, I learnt the songs but I learnt so many things. I received stories, I saw pictures, I received vocabulary, dialects, the notion of what words you can’t use, I received the idea of what I can wear and what I can’t wear—much less for me and more for the girls. All this was being received in this classroom and then you had my home and my school where—all this is very reductionist but bear with me—philosophically, the attempt was to create a space that is non-denominational or not identity driven. So, were these different cultures? Or were they interconnected somewhere? We think this is diversity but I believe that this is not diversity because they are all cradled in the establishment. By default, they are cradled in certain establishment values—whether it is my school, home or Mylapore—they actually share foundational notions of culture, habit, acceptability etc. So in this experience of learning music, I never felt at any point that I was away from anything even though the language I used there was different. There was no problem in Carnatic music existing anywhere because Carnatic music has to exist everywhere: nobody challenged that notion. We will come to the other art forms or rather cultures soon. In fact, that it could exist is in many ways its strength which means I can exist anywhere—most importantly, not the music, I can. So, my culture or what I inhabit—or in my case because I am an artist I share, I propagate, I perpetuate—can actually exist anywhere and if it doesn’t exist in some place then it is aspirational for that space and those people to want it to exist. I think this is how we have constructed culture in this country for a long time and this is not new. What are the qualities then for me or for a culture to exist everywhere? Are we looking for certain boxes to be ticked? There are of course specifics of the subcontinent you can look at, but in our case we would talk about notions of purity, antiquity, oldness—this is where the word classical comes in, which I detest using and don’t use at all because it has no relevance to what we are discussing.

Classical, in my opinion, is entirely a social construction and not an aesthetic construction, similar to folk. We have come up with this notion of some cultures and ideas being classical, some ideas being folk. But what does it mean? We may look at oldness, we may look at who is practicing it, we may look at how pure it is: all these words we build on practices and those that kind of accommodate these words will come into this practice. Now, the amazing thing about cultures that are accepted or dominate is that if there is any benefit, it accrues to everybody in that culture—that is the astounding thing. Say I represent this culture—everybody like me in this culture will benefit from it but the inverse doesn’t work. So the reason you are creating a certain culture is you are also curating who can participate in it and what are the qualities required for someone to participate in it. One would also like to participate in it because they see that by participating there is community benefit that accrues to every individual—why would anyone refuse to be part of it? So it is not just an aspirational model but also a beneficial model that helps everybody in that group and therefore you want to belong to that group. You want to applaud when everybody else applauds, you nod your head like you understand something is happening when you don’t know what is happening and I’ve seen that many times in the audience—sometimes, it happens at the wrong moment and everybody does it at the wrong moment together. But why do they do this? It is not just some group mentality. It is you knowing that the idea of knowledge is a very important part of knowing—that even pretending to know helps in participating. So when we constantly talk about diversity, it is the biggest fraud because the word diversity is used after the establishment is established. Now if I say there is no establishment, does diversity exist? What is the point of reference for diversity? It is very interesting in the way we perceive it. I am not talking about it semantically. Diversity is seen from some positionality. You establish something as the norm—it could be caste, race, gender, ethnicity, colour, anything—and then you say that this is not the only thing but there is so much more. But if there is no norm—in a completely hypothetical situation, then everything exists and we are not dealing with this question of whether it is diverse or not, whether we are diverse or not. Are we homogenous, then? This whole question does not arise. So, the foundational point of the conversation becomes a big problem.

One of the explanations that people provide as to why certain things are in certain places—in spatial connotations, because that is how we separate ourselves culturally—is a phrase that is especially used for art, is that it is about taste and preference. You are not looking at the fact that this is not part of a philosophical problem or a social problem. One defends his choice of music saying—I have listened to it since childhood, so I like it and it is about taste. But what is taste and preference itself? This brings us to my first line—it is a cultural habit, it is constructed. In terms of food, music, we say certain things are special but what is special, why it is special—nobody really knows. The other word I want to bring in connection here is a word used very loosely by artists: ‘aesthetics’.

We have conflated aesthetics to mean beauty—we all use it casually. But aesthetics is not beauty at all. So, if you actually look at the Greek words that come with ‘tikos’, they usually mean it is a body that has come out of some kind of empirical understanding. In this case, it would be experience and observation. So, aesthetics is the principle behind the art, behind the practice or behind the idea of beauty itself. We are looking at form, construction and what I like to call intentionality and there is intentionality to every practice we have whether we realize the intentionality or not. This is very important to understand because most of the times, the dominant is constructed with this presumption that it is beautiful—beautiful used in the larger connotation, not just in prettiness—and we are participants of that. I always like to say that all homes in India are ‘FabIndia homes’ today—just think of the earthy colours we believe to be Indian colours today. There is something fundamentally wrong with it. For example, if I go to a village in Tamil Nadu and I see a person in a polyester kaftan, I think it’s ugly—my instinct tells me it’s ugly immediately. Is it out of taste, is it habit?

I come from a position of the establishment and we do this on an everyday basis. I have heard so many people say fluorescent pink houses are ugly, it’s not in our culture. What are we now talking about? Most of what you have constructed comes first from the experience of it, not from the intellectual understanding of it. We react to it—we react to a colour, to a song, we react to the way a person speaks, the dialect of a person—we decipher everything in this country by just those things unless we are willing to see aesthetics as something far beyond. Now, Mukesh Ambani’s house is ugly, it is unaesthetic and I will tell you why it is unaesthetic—not because I think it is ugly. It is unaesthetic for two things, one primary thing and I will stick to that: it is insensitive to the context of its construction, it is insensitive to where it lies, to who sees it. How does it embody the space that it is living in? That is part of the understanding of what is aesthetic. I do find it ugly but that is not the reason I am critiquing Mukesh Ambani. So, we have to understand the role that these observations and perceptions make in the way we have decided beauty, ugliness, culture, not so cultural, less cultural. How do we then segregate culture other than the hierarchical manner we do it in?

One of the most important things that an artist needs to do is to create illusion. The entire idea of art is illusion at the level of practice and so, ‘suspended disbelief’ is a very famous term associated with art. But why this an illusion? People tell me that when they saw a particular play or heard me sing, they were in a different world. That is a fascinating description. I have also often heard: ‘After a tough day’s work, your music allows me to find peace’—this shows that there is a necessity to separate themselves from reality. Art is able to create illusion and this is not different from many other cultural practices. For example, the puja done every day is a religious, cultural and spiritual practice. But in the process of offering flowers to the deity, the person, in some way, is removing himself from reality, at least momentarily. The question here is: Are we really creating an illusion?

I would prefer to say that beautiful art is abstraction rather than illusion—instead of taking us away from reality it allows us to see reality in a way in which we are not personally engaged. If there is some violence I have participated in physically, I cannot understand that violence because I am party to it, but when I see that as the idea of violence through a piece of music or a dance performance, my perception of violence is detached from my own engagement. This, I believe, is the most important role played by art. As an artist I would think this to be a very important role for myself.

In the hierarchy of art and culture, there is something quite violent we do. The top bracket—of culture, artistic experience and inhabitation—tries to take the body out of the conversation and as we go down the societal chart, the body as a material is out. So, the accent is always on the non-material which is the mind. This is not unique, you can see this across the globe in any culture. This could be in the practices that we do. For example, a classic case is that many upper-caste Indians prefer the word spiritual to religious. They are so intertwined that you actually cannot separate the two. But why do they prefer the word spiritual to religious? Because religious is material and spiritual is not—it gives them an entry point to remain detached from the ugliness in which they are a participant. This, in a way, elevates them too. Many times have we heard that he is a very spiritual person; we have seen hilarious Twitter handles such as ‘Indian spiritualist’. There is no understanding of why you would want to say that. It is because you want to be identified not like the religious Hindu or the religious Muslim or the religious Christian—rather to be identified as one who is slightly above, looking at the universality of human experience as a spiritualist. This is what happens at the upper echelons of the social structuring. But the worst part of it can be seen as you go down cultures where the violence occurs—and I am using ‘go down’ cultures very carefully, not judgmentally because the construction of cultures is such. Here the mind is removed and the body is further accented. It is very similar to what we do to labour.

As you go down cultures, we talk about the body being important, we say, ‘it is physical’. This is something that a great koothu artist called P. Rajagopalan told me and it shook me when he told me. Katya koothu is a kind of sacral theatrical form which you find mainly in Tamil Nadu and some parts of Andhra. We were having this conversation on art and suddenly he said, in Tamil: ‘for me, art is labour’. It shook me because I have never used the word labour with my singing—even my practice is sadhana, which means something else and has spiritualism attached to it in some manner. But I was in tears when he said that to me because it did something to my stomach. So, I asked why. He said that some part of the art production is also a caste obligation, therefore it is labour. But the idea of you making this incredibly complex art object every time you perform is not seen as something I would call elevating. It is seen as hard labour, as physical activity like a carpenter’s work or anyone else’s work. I have never said that about my work and I would never say it. I am on a podium constantly. So, this violence is very important for us in order to notice the ways in which we construct culture. The removal of the body and the emphasizing of the body does something even more drastic—it erases the mind. The moment you erase the mind of a person, the person does not exist. Here I will speak about the people who make the mridangam, which is a two-sided drum. They are not seen or spoken about—I wrote a book about this called Sebastian and Sons. Even two years ago, they were called repairers, not makers. All mridangam artists will say ‘Go to the repairers’ shop’ but they are the ones who make the mridangam—they get the cow skin, goat skin, buffalo skin to make it—but their mind is erased in this conversation of who makes the mridangam. Most players, by the way, come from the Brahmin community, maybe a few from other privileged communities. And it is always the player and never the maker that speaks about the making of the mridangam.

Erasing the mind is a huge violence. I have said before that when the privileged participate in the established culture—with the little elasticity that exists, the benefits accrue to everybody. The reverse of this is also true: In the case of marginalized cultures, the disgrace accrues to everybody. If there is one person from a community that is marginalized who has probably done something, the disgrace, assault and attack happens to the entire community. This is exactly the opposite of what operates in the case of the establishment. This, of course, compounds itself as you go further down the ladder. I was in Rajasthan last week and we were discussing culture, art and what interventions are possible etc. Most art forms in Rajasthan are practiced by marginalized communities, many from Dalit communities. Now, it is very interesting—we celebrate Rajasthan as this place of colours, we say, ‘oh, what art!’ But what about the artists? Where are they? Is it their culture that we are celebrating or are we celebrating something we are seeing? Whose culture is this? Their lives have not changed. If one Manganiyar has become world famous—you’ll hear that all Manganiyars are now doing well. It does not work the other way round. Only that one Manganiyar will make a living and the rest will be within the bonds that are constructed around their cultures. So how does one create a conversation there? It is a very important and complex place. It might seem like a very grim picture of everything, but what about crossovers? I have heard examples of the ‘Ganga–Jamuni tehzib’ for so long, so there have been cross-overs and inter-relations.

Nobody can deny that there have been interesting conversations and important crossovers, but often, the celebrations of the crossovers are post-facto. We hold on to that celebration for us to retrieve something from today—which is what we are doing today in India, which I believe is a tricky route to take. There have been beautiful exchanges across caste, religious and political lines. Yet, they go unrecognized unless people who are part of the establishment participate in these exchanges, only to come back as memory after the culture has vanished.

Sometimes, I am scared of the act of archiving because there is something very depressing about it. When somebody says you have to archive, it means that the thing is gone. Nobody says, let us find a way to keep it alive within the community. Rather than saying ‘let’s archive it before it goes away’ we should be looking for ways to empower the community to have it within their own world and on their own terms. In case a community discards something, we need not lament that we lost those beautiful songs, because if they want to discard it, they should discard it. Take, for example, the fisherfolk songs. Many fisherfolk songs are gone and I have heard so many people say we have lost all those things. People like me who have never heard a fisherfolk song in our life will say this. But why did it go? Because they got motorboats. A lot of the songs were labour, because they used to row and they were in the sea; while rowing, they wanted to see what is around and smell the air because that took away the pain of physical labour. Then motorboats came in. Who is to make that decision if it was a loss or gain? I think it is a gain and if there is anybody who should say it is a loss—it is the fisherfolk, not me.

I will conclude with two things. One is: How does one deal with these dichotomies within oneself? Personally, I love my music, I love singing—I love every moment of the song but I am also completely aware that there is an othering nature in my music. To me, both of these are realities. So how does one have a conversation between both these realities? You may tell that it is constructed—of course it is, but it is also a reality. I am passionate about the tune, the raga—I would spend hours on it but I know that the raga is also othering. I think we have failed to create conversations in these very important spaces. Being reductionist in terms of cultures and labelling things as casteist—it is not as simple as that. What is the conversation in-between? Or how do you change the practice in order to accommodate a larger conversation? A very important component here is faith. With faith, we have to look at the in-betweens because in faith—in Tamil, there is a better word, sarang i.e. ritual—there is that habit, that little thing, maybe a little action or a little moment, whether I believe or not. All of this is caste and gender bound—yes, but what is my conversation there is what I am asking, just like I am asking what my conversation is with myself. Who is having that conversation is a very important thing, but what is the conversation? Do we have a sensitive conversation to create a bridge or do we have a discarding conversation to say this should be thrown out? In which case, you are not engaging with it, you are also constructing another culture. So when we say ‘constructing democratic culture’, I am really scared because what do you mean by ‘constructing democratic culture’? What are we saying in this sequence of words? Is a democratic culture something to be constructed or is it the deconstruction of construction? I’ll leave you with that rather bizarre statement.

Question and Answer Session

Audience 1: Thank you sir, for such an enlightening talk on a vast subject like culture. My question is: Is it the diverse culture of India that makes us strong? As you said, you were able to sail through from your school to your music class and so on.

Thodur Madabusi Krishna: The presumptive word in your statement is that we are strong. But are we strong?

Audience 1: We are culturally rich.

TMK: But how are you so sure? We have diverse cultures, yes but does that mean you are strong? Where are these diverse cultures? How much have you or I engaged with diverse culture as individuals? We like to see pictures of many things, such as, Naga dancers everywhere when any dignitary comes. But my question is: Are we strong? If we are not going to challenge that, we cannot start with the presumption that we are culturally strong. Despite the diverse cultures I think we are weak because we don’t engage with the diverse cultures respectfully and equally. Until then, we will remain weak. India itself is a notional idea, let’s be very honest. We may accept the idea but it is a notion, as abstract as freedom. You can never answer the question: What is India? I always say, whenever you land back in your city there is this feeling, that smell—it could be a stench but you still love it. If you came by train to my city, you could always smell the Cooum River and the moment Cooum came, we knew Chennai has come. It was stench but it never bothered me. It is this feeling of home that we have constructed as India. We have created this India. In this notional picture we are drawing, we are very lucky but we are very weak because if we were really strong, we wouldn’t be having this conversation here today. In fact, I wouldn’t be speaking. The fact that I am speaking means we are weak. Upper caste man talking about culture, also having the audacity to talk about cultures he has no association with—this is sheer societal arrogance, I’m placing myself on the dock here. So, let’s not presume we are strong because the moment you presume you are strong, it allows for narratives to say why you are strong and then there is one narrative we will all follow, such as everybody having a flag at their home—that is a classic way to say you are strong. Every (social media) account has the Indian flag today—why? It’s because we are diverse but we are not strong.

Audience 2: Loved your mesmerizing talk. The way you define identity in terms of different kinds of cultural contexts by setting terms and conditions. Different cultures are claiming that they have different identities from one another. If it is so, they are not in the same place. I know they are based on certain kinds of regular norms that they are all establishing and accepting certain things but they are not in the same hierarchy. There is an aspect that is keeping them in different layers of certification. That was on the question of the brain and the mind. It was more quasi-biological scientist’s voice and then this whole idea of consciousness came: where is this coming from?

TMK: This was asked as a scientific question. I think the existence of consciousness is power: the moment you are conscious, power exists. It is at every level—individual level, community level, family level. So, power is at the underpinning of anything in society and anything we establish for ourselves, because power is the trigger of identity. You can’t take identity and power out of it either way, whether you are the one who is enforcing it or the one at the receiving end. But the amazing thing is that despite all this, we find moments to be free of that power. Most marginalized art forms in the world have been robust, asking very strong philosophical questions about identity, society, politics etc. Why have they done so? Because they have no choice. Nobody is going to listen to you, so you write frontal poetry, you do your movements—your body, your songs—everything is to make a point to the face. But you ask that artist—the one who is being marginalized and oppressed, pushed to the corner right through their lives, from the moment they are born they are told who they are, where they should be, what they should wear, where they should not work etc.—what happens when they dance or when they sing? And that is what is interesting. They will say, at that time, nothing of this is in operation. So, are they unconscious? No, they are very conscious. Somehow, the issue of power—whether it is in facing oppression or enforcing it, dissipates momentarily. That is why we have these in-betweens in culture, not just in art but in culture in practice where momentarily it can disappear even if you are a person facing the worst. I am not making this up to create a conversation. I have heard this from artists from marginalized communities. You ask them what is happening at that time, they will begin to say that time is just... then they will stop, there is no word there. That is interesting.

Audience 3: I can’t help but make a comment before I ask the question. I think you are a brilliant speaker but you also intimidate the audience and I begin to think that we must be doing the same in our classrooms. Anyway, I’ll risk it. I want to ask you why we can’t celebrate the advent of motorboats as well as mourn the loss of those fishermen songs?

TMK: My point here is a question of some amount of emotional intellectual agency because those two co-exist. This comes, then this will go; there is no other choice in the matter. So the problem is you know that the causality is here. You can say you are mourning the loss of the songs but the causality is the motorboat—that is the knot we are unable to handle. We know that the motorboat is good, we cannot deny that it changes their lives. But I would also question if you should mourn. I’m not saying I’m right but let’s raise this question: What are you mourning? Is it some kind of an imaginary romantic idea? We don’t know. But if the fisherfolk is mourning, it is a different deal altogether because it is their life—they have sung it every day; they may find a different way of keeping it alive if they so feel. I know one Manoharan Anna. He sings all those songs happily, he loves to sing them. Nobody else sings it. He is mourning the loss of the song because that is his life. But what am I mourning? I feel, sometimes, I am mourning a romantic idea of that—a romantic notion that something beautiful is happening when they are going to sea. The song is also drudgery at some level. It is physical effort. I haven’t done it, I don’t know what it is to row the boat and sing the song? Maybe until I row the boat and sing the song, I should wait.

Audience 4: You are saying that there is no diversity outside of the establishment: it is the establishment that creates the norm and then we look at diversity from there. But I am a little confused. Isn’t there diversity in the Krishnamurti school and in Mylapore and haven’t you emerged stronger because of them?

TMK: Those are two different things you have pointed at. This idea of defining diversity comes from the definition of what is established. The diverse or let’s just say the various exists, but what that various is, where they exist, how they are mapped are all entrenched in the word diversity. It’s not just that there are multiple things entrenched in the word—you are also looking at where they are and that comes from the establishment of the norm. Of course, studying in a J. Krishnamurti school and being part of the Carnatic music world are two different things. At the surface level, they are two worlds but they are both entrenched in certain unquestioned ideas of culture, behaviour and belonging. These ideas exist at the foundational level and we have to be conscious of them. To believe that the Krishnamurti school, for instance, is somehow this liberating world that I studied in and Mylapore is some claustrophobic traditional world and I am struggling between these two worlds is not true. There is probably some liberation here. But foundationally, between both of them, there are lots of unquestioned accepted things—but they still exist.

There is probably some liberation here, but foundationally, there were lots of things accepted without question and such things still exist.

Audience 5: Could you talk a little bit more about the unease that you mentioned between art and labour because then, in one of the previous questions you were answering, you spoke about how even for artists coming from the most marginalized communities in that one moment of performance everything kind of disappears. So how does one navigate that?

TMK: That is very interesting. That question should not be answered by me, me answering that question is problematic because I am not an artist from that community, I have not experienced what that artist from that community has. So take whatever I say with a bucket of salt because I don’t know. There is a consciousness that it is labour because of societal situation—even if it is not labour, it is a compulsion of social pressures. For example, you have to sing these songs to make sure that somebody listens to you. The pressure applied in different ways triggers cultural expression but when the expression happens, somehow the pressure disappears momentarily. So, is that freedom? The sociologist will say that it is not freedom, but compulsion. But am I going to diminish the agency of the individual who says that at that moment they feel free? How does one navigate that? Any kind of absolutism cannot navigate that, rather an in-between is required, because in that experience there is a possibility for a more robust conversation and reflection by the observer. Many other things will seem to be possible from there. You could ask the same question about music or dance or work done in the fields—a whole day’s labour, planting of paddy. At one level it is physical drudgery but is there anything else to it? What makes that person smile? I don’t know an answer to that question. All I am saying is that don’t presume that all of this exists in leisure and these echelons of great culture. It exists in every space with its own possibilities. It doesn’t only exist because I have the time and leisure to come and sing or to practice certain cultural habits. They exist in every one of those things and a respectful learning from every one of them will make our cultural conversation stronger. Maybe then we can say what you said.

Audience 6: I am mesmerized by your talk, so I don’t know whether my question will make sense. Imagine that you were the principal of a school and you were asked to create a curriculum for your students which has to be ‘holistic’ and has to really make sure your kids are growing up with the true idea of ‘culture’. This school is also a very democratic one. It has a student council that co-constructs the curriculum and this student council tells you they want only Bollywood songs and Bollywood songs which have deliberate innuendos and they want to dance a particular type of dance which people frown upon—and you as a male upper caste establishment principal, what would you suggest that the curriculum is?

TMK: You were not mesmerized at all. You trapped me brilliantly, very well done! I am going to try and don’t ever share my answer with anybody because I am sure I’ll fall on my face. There are certain aspects of what you said which will have a different outlook because you are looking at children. There are certain things that change when you look at that paradigm—they are 12, 13, 14-year-olds—so there are certain things we will restrict, if that is the word. There is a certain growing up time that is happening for which we will look at it, whether it is innuendo or especially sexually explicit things etc. But having said this: I have to know the context. First, you said you have a student council—where is your school situated? Give me an idea of the gender, caste, identity, diversity of your students and tell me if that diversity is represented in your council.

Audience 6: Depending on your answer, 1000 students may be doing things differently next year, so please be careful Sir. My school is situated in an area of Kolkata which is not really Kolkata but in the suburbs. The national Hindu–Muslim ratio is skewed here—we have more Muslim students; pretty much 50–50 in terms of gender; very challenged in terms of economics because their parents used to work in factories which have shut down; absolutely lower middle-class parent community. A few parents have been attracted by our curriculum but very few. The student council is elected through a combination of nomination, interview and election, giving rise to a not so diverse council.

TMK: So, your problem starts there. First, your council needs to be diverse and more representative. We are talking about the cultures of the sounds or what they want. If they want Bollywood, I have no problem with it. Like I said in the beginning, I would look at the content. We are looking at a school where there are children, not adults who can make those decisions. For example, if there is very high sexual innuendo, that is fundamentally a problem because that objectifies women. So those are issues we have to be concerned with. But being bothered by the Bollywood sound is a problem: you can’t be bothered by it. It is possible that even in that sound you could get songs and ideas that are important. We have this tendency of discarding that as being of a certain nature. I wouldn’t do it. I wouldn’t enforce Rabindra sangeet, for example, as being some epitome of value. Some people think it’s the same tune set in different ways but that is a different thing altogether. But that apart, I get where you are going with your point in the question of what Bollywood represents. I don’t even care about the classical. I think it is possible to engage with even that on our own terms. Actually, what is Bollywood? When we say Bollywood, we are talking about a certain commodification quality that it represents but that commodification includes gender discrimination, objectification, casteism etc. If it is an idea of cinema we are talking about, then it is more important. The same battle is in Tamil Nadu for example, where Tamil cinema is so dominant in the cultural mindset of children but many schools will say no cinema songs. Why not? I think there is something completely wrong with that because there is a cultural snootiness to it. You make sure that what is being said is within the ethos of equality, fraternity and everything that we want but we can’t discard that sound, colour, moment because that only discriminates further. You then create a dichotomy and a huge chasm between the school and the home. Often, we hear this: there must be music in schools. I always ask, which music? When they say they have music in their ears, I know what music that is. Suppose there was only rap, would they still say there should be music in schools? They wouldn’t. They mean classical-like—whatever that means.

We cannot shun Bollywood as a social evil. While we must include songs from Bollywood that are ethical and do not discriminate or oppress, we must keep in mind that Bollywood is also a majoritarian monstrosity. We cannot allow it to swallow all other ideas of music. Cinema music is far wider than 'Bollywood'. Cinema comprises multiple cultures. Populism cannot drown diverse voices in any area of human activity.

I would say I hope I hear some lovely film songs in your school if I come next year.

Thodur Madabusi Krishna is one of the pre-eminent vocalists in the rigorous Karnatik tradition of India's classical music. As a public intellectual, Krishna speaks and writes about issues affecting the human condition and about matters cultural. He is the Founder Trustee of Sumanasa Foundation, established in 2005, with the objective of engaging with the arts and the community. Sumanasa enables communities to develop culturally vibrant spaces and create platforms that present artists and art forms from marginalized backgrounds. It helps create different avenues for artists to engage in social dialogue and in building appreciation and interest in the arts. In 2016, Krishna received the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award in recognition of ‘his forceful commitment as artist and advocate to art’s power to heal India’s deep social divisions’. His path-breaking book A Southern Music – The Karnatik Story, published by Harper Collins in 2013 was a first-of-its-kind philosophical, aesthetic and socio-political exploration of Karnatik music. He has been part of inspiring musical productions and collaborations that are unique and unusual aesthetic conversations between art forms and communities across social spectrums.

Comments